Elon Musk tweeted an image a while back listing 50 cognitive biases we all face. And whether you’re a founder, investor, or an employee, it’s useful to remind yourself of what these biases are, and how they can effect your decision-making processes. In the coming weeks we’ll take a look at a few of them:

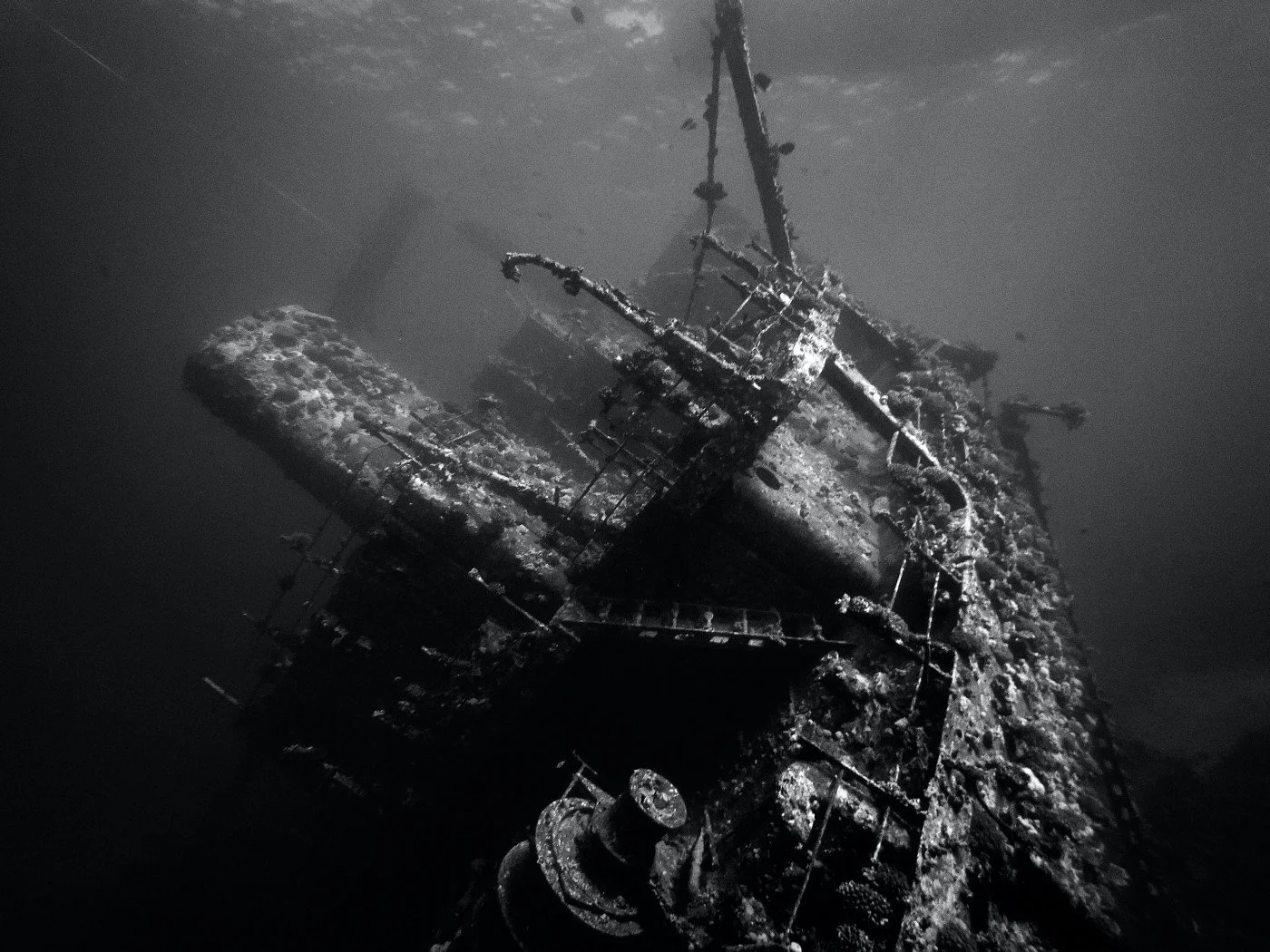

Sunk Cost Fallacy

I happened to be reading Psychology of Money again, and one of my favorite parts is about sunk costs. Author Morgan Housel says “We should also come to accept the reality of changing our minds.”

The text book definition for the sunk-cost fallacy is: “the phenomenon whereby a person is reluctant to abandon a strategy or course of action because they have invested heavily in it, even when it is clear that abandonment would be more beneficial.”

A vivid example from the book is those of us who stay loyal to a career because it’s in a field we chose at 18 when deciding on a college major.

Morgan says:

“… the odds of picking a job when you’re not old enough to drink that you will still enjoy when you’re old enough to qualify for Social Security are low.”

Curse of Knowledge

The Curse of Knowledge occurs when an individual communicating with others assumes they have the background and knowledge to understand what’s being said. Simply put by Shane Parrish, it’s the inability to put ourselves in the shoes of someone less informed.

At a technical level, experts organize knowledge differently than novices. The experts often infer knowledge on the part of the novice and wind up omitting the reasoning behind how they arrived at their understanding of a variety of complex subjects.

The term “curse of knowledge” was originally coined in 1989 by economists Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Martin Webber in an article published in the Journal of Political Economy.

There’s another side of the coin. In addition to assuming others have the knowledge we do when communicating an idea, the curse of knowledge can often stop us from sharing ideas altogether.

Derek Sivers describes it as “obvious to you, amazing to others.” In his book Hell Yeah, or No, he says, “Everybody’s ideas seem obvious to them … So maybe what’s obvious to me is amazing to someone else? … We’re clearly bad judges of our own creations. We should just put them out there and let the world decide.”